Bitcoin for safety

24 Aug 2019

Starting in 2008, central banks injected an unprecedented amount of new money into the global financial system. Along with big gaps in wealth distribution, this has created profound systemic risk. The last few months have shown indications that this risk is starting to come to the surface.

The setup in front of us is not for a garden variety recession. It’s for potential cataclysm: a drawdown that will hit normal investors hard, but retirees and pensions especially so, threatening the premise of our financial system. This crash, or even just the threat of it, will lead our governments to take extraordinary action in an attempt to avert a long depression. That action will cause an incredible level of inflation.

As I’ve watched the following events play out, some of the only optimism I feel is due to the emergence of Bitcoin as a nascent asset class. I see this new tool as one of the only potential safeguards that people in normal income brackets have against the kind of trouble I’m forecasting.

As I lay out the narrative I've watched unfold over the past few years, I'll occasionally interject with observations (formatted like this) on why I think Bitcoin is going to become increasingly important, even relative to traditional safe-haven assets like gold. After reading a draft of this post, my brother lovingly dubbed this "the shill zone," and I don't disagree.

It should be obvious, but as an explicit disclosure: I am long Bitcoin.

Welcome to negative

It’s an exceptional time in economics. Negative-yielding bonds have passed the $16 trillion mark for the first time ever. Germany’s flagship 30 year bond yield has gone negative, also for the first time in history.

"$16t in negative yielding debt & rising not good for managers of long-term liabilities such as pensions & insurers. AUM for all developed world pension funds stood at $27.5t in May 2019. In countries w/ negative yields, pension funds’ AUM totals $4.7t" https://t.co/faE5Eiy6zb pic.twitter.com/hXmbq8KkhP

— Trevor Noren (@trevornoren) August 24, 2019

This means that investors are paying governments (and some companies) for the privilege of lending them money. I pay the German government $10,000 today and in thirty years I get back $11 less. Intuitively this doesn’t make much sense: given the time-value of money, cash I have on hand now should be worth more than theoretical cash in 30 years, at the very least because I may not be around in 30 years to spend it.

And besides, there’s what we call “counterparty risk:” the possibility that the German government might not repay me (admittedly a low likelihood) or the possibility that the euro will have suffered significant inflation since then, reducing the real purchasing power of my $10,000 (a much higher likelihood). The risks of lending money for 30 years should be offset by some reward, but with negative yields the lender is penalized for assuming this risk.

This may not seem like such a big deal, or at most a weird abstraction more or less confined to finance people, the kind of people who worry about bond yields and think in basis points.

If only.

Negative yields dramatically affect, for example, retirees because traditionally retirees have held a lot of money in “fixed income,” or bonds. The deal was that you spent your prime years earning, saving, and maybe investing in risky assets (equities) and as you got closer to retirement age, you flipped most of your allocation to less risky investments that yield a consistent return - i.e. bonds. This ensured that your hard-earned savings wouldn’t evaporate in an equities downturn.

Since negative rates eat at savings instead of paying out, retirees—and pension funds, but we’ll talk about those later—are driven towards keeping their money in risk, or equities and lower quality credit, and basically having their savings exposed to the stock market and all its associated drama:

These low rates have been great for borrowers including countries, companies and mortgage holders, since the cost of servicing debt has dropped. On the flip side low and negative interest rates have been bad for pensions and retirees who are trying to generate enough income from their assets to meet their liabilities through lower volatility bonds. These groups need to buy riskier assets and embrace that they will need to accept more volatility in order to achieve their goals.

The bottom line is that no one really knows how this will end up since we’ve never seen it before.

Negative rates are strange and disconcerting in themselves, but reconstructing their cause reveals other big problems as we’ll see in a bit.

This is what Bitcoin is for. Bitcoin, like gold, is a "non-productive" asset, a commodity. This means that it doesn't in itself generate yield, though obviously there's been plenty of price appreciation over its ten year life.

For reasons I'll describe shortly, this new asset is a possible tool for countering increasingly negative yields and diversifying savings. A 1 to 5% allocation lets you simultaneously cordon off risk to a small percentage of your portfolio but retain exposure to considerable upside. It's the barbell doctrine incarnate.

Instead of risking a huge portion of your savings in equities for positive return, you can use a small amount of Bitcoin as a metaphorical call option on a new asset class – an asset class that isn't affected by the same vulnerabilities that have created the negative rate conundrum, in addition to the other maladies we'll get around to later.Owning bitcoins is one of the few asymmetric bets that people across the entire world can participate in.

Why should I ever hold stocks? 5% #bitcoin + 95% cash outperforms stocks on risk AND return, every year past 6 years... pic.twitter.com/WbB3n1VZLy

— PlanB (@100trillionUSD) June 7, 2019

How did we get here?

So this $16T pile of negatively-yielding debt is something that’s never happened before, and based on common sense it seems kind of unnatural. How did it happen?

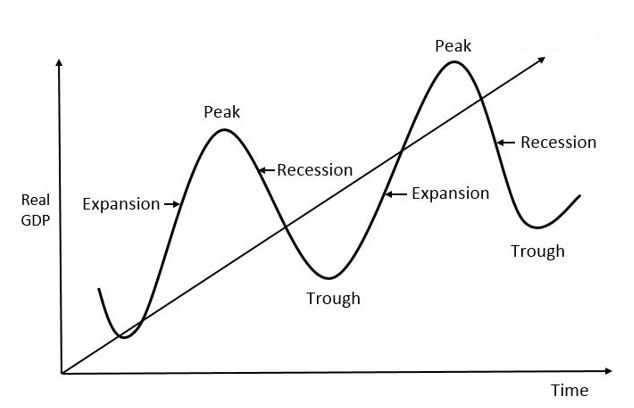

For the past 30 years, governments and specifically central banks have been a lot more active in monetary intervention (i.e. influencing the money supply) in an attempt to be counter-cyclical. This means that governments basically want to smooth out the booms and busts that the business cycle is naturally subject to.

When a recession or depression happens, the central bank steps in and “provides liquidity,” meaning they inject cash into the banking system by doing things like buying US debt instruments from certain banks at above-market price. This gives the banks extra cash on their balance sheets to lend out, and so lowers the interest rates on pretty much everything else. This introduces unnaturally cheap credit that is supposed to stoke the economy by encouraging people to buy more things and take out more loans.

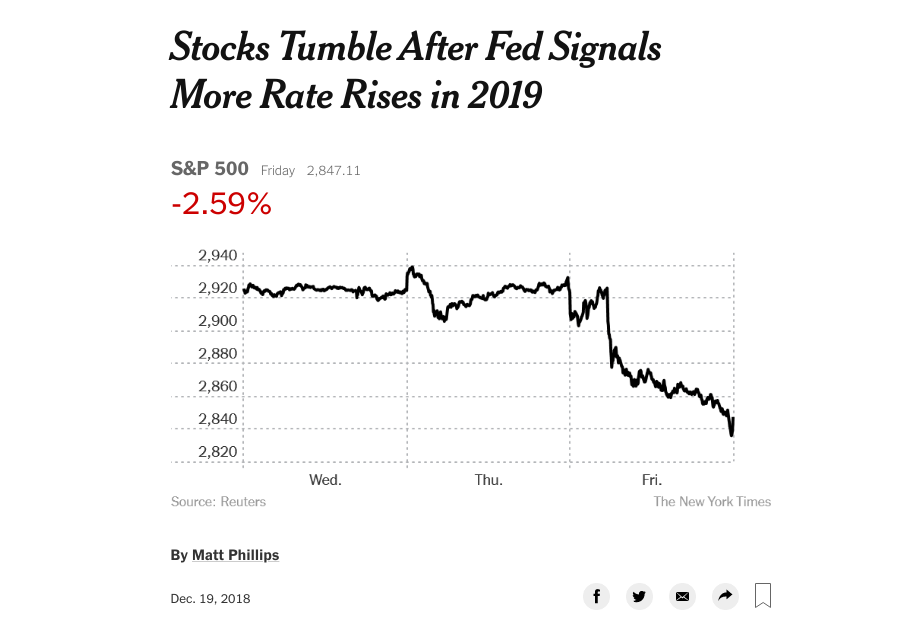

When the economy is running too hot, the Fed (the US central bank) raises the price of money and limits credit expansion, though they haven’t done much of this in the past 20 years. As we’ll see, the economy has become reliant on cheap credit in deep and interesting ways.

The economy will no longer tolerate rising interest rates.

Post 2008

Central bank intervention came to a fever pitch 11 years ago. The 2007/8 financial crisis was so bad that the Fed went beyond its usual measures. It drastically upped its purchase of US Treasuries (debt) and started buying things like mortgage-backed securities.

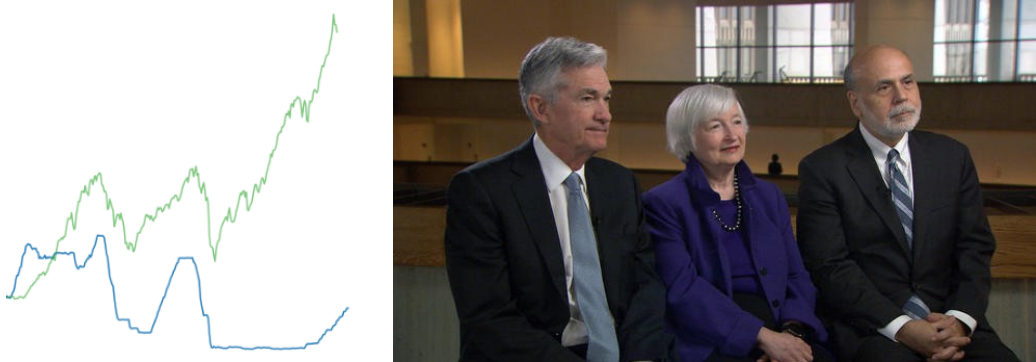

The chart below shows the level of our monetary base, or the amount of currency circulating plus the level of reserves banks hold at the Fed. This is one of my favorite charts of all time, it’s just insane.

Shaded gray bars are periods of recession.

The tricky part about central bank intervention is that it’s a discretionary process driven by a relatively small group of people. How much intervention is too much? In 2008, the answer seemed to be “almost no amount is too much.”

As you can see above, this resulted in the supply of base money roughly quintupling. Why we didn’t see crippling inflation is another story for a different blog1. Even though we didn’t see traditional (and I would argue deceptive) measures of inflation like CPI and PCE spike, all this extra “liquidity” has led to systemic bubbles in important asset markets like real estate

and the stock market.

So now the housing market is more overbought than before the crash in 2007 and the stock market is… well, almost two and a half times more overbought than ever.

The root of this being that well-intended central banks are trying to protect us from the volatility that comes with the natural ebbs and flows of the business cycle.2

Our friends in Europe have basically gone through the same process, except instead of attempting to “normalize” and tighten credit in the last few years, they’ve had to double down on easing in order to stave off collapse, probably due to intra-EU debt problems.

This is what has created deeply negative bond rates in Europe - the European Central Bank (ECB) has been aggressively purchasing bonds in an attempt to inject cash into the economy, which drives bond yields down and in the process hurts anyone relying on fixed income.

This is what Bitcoin is for. Bitcoin's monetary supply can't be expanded by anyone, let alone a small committee of economists. There will only ever be 21 million coins minted. Nobody can decide to try to tame credit cycles with "counter-cyclical" monetary policy.

Because Bitcoin's monetary base cannot be increased, once you have a certain fraction of Bitcoin's total supply you will always have at least that fraction. It is literally the only asset ever to have this property, and this fact alone makes Bitcoin extremely unique. As a result, some people refer to Bitcoin as "the metric system for value."

Hair of the dog

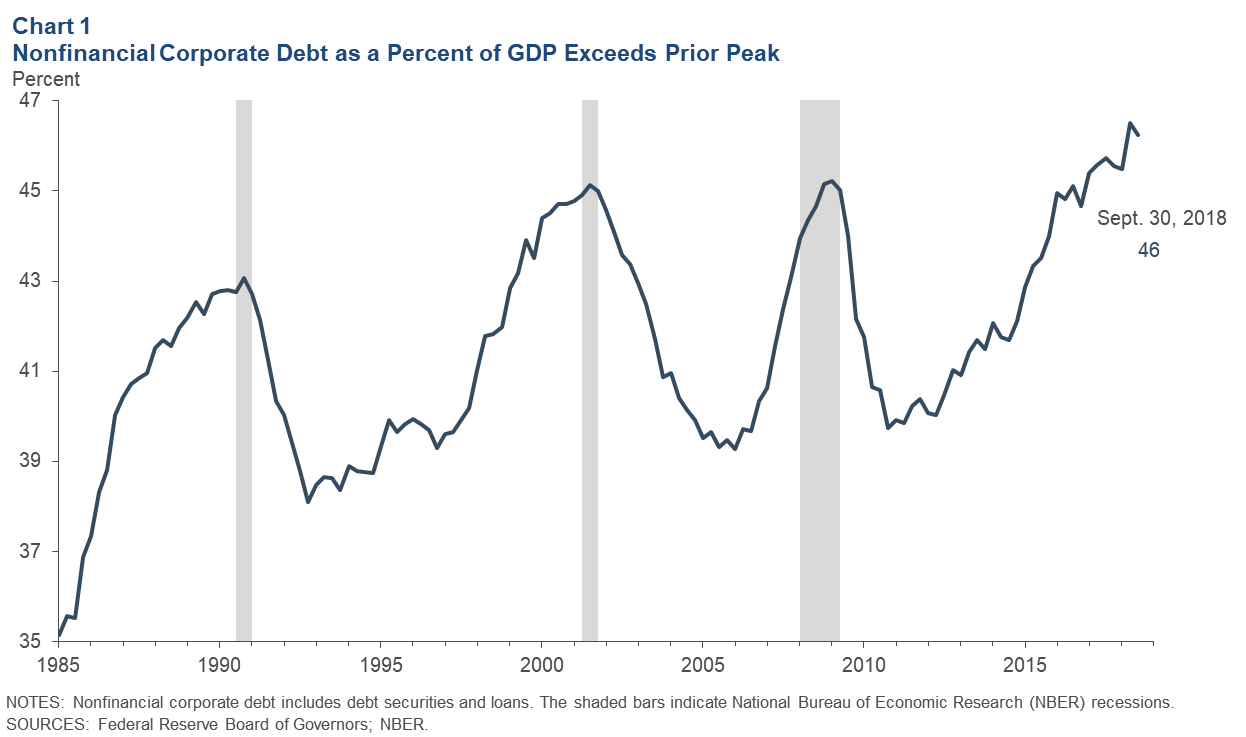

Injecting trillions of dollars into the money supply isn’t something we can easily walk back from, since the resulting availability of credit has allowed our economy to stave off slowdowns by increasing “leverage,” or using debt to fund expansion.

Shaded bars indicate recession.

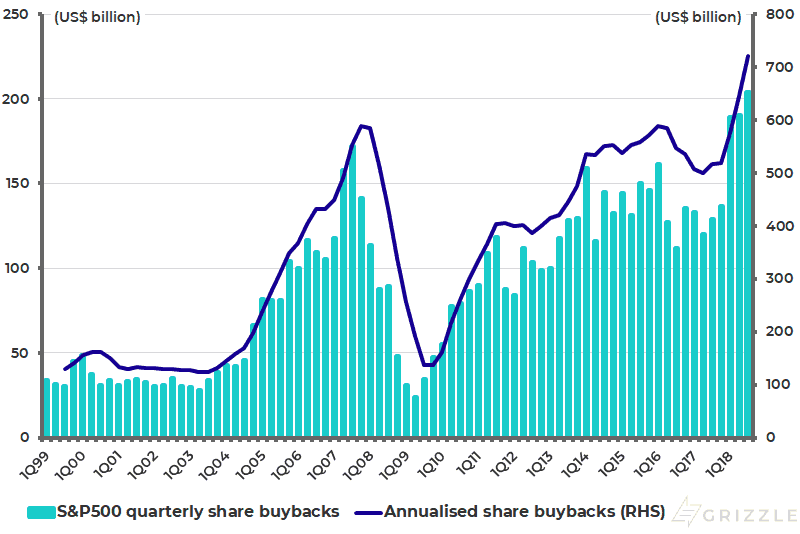

One way this cheap credit is used is for leveraged share buybacks, a term you’ve probably heard recently. In a nutshell, this is when a company takes advantage of favorably low interest rates (enabled by the central bank’s intervention) to take out a loan. Using the loan, the company buys back its own shares which (definitionally) reduces the number of shares outstanding and artificially boosts earnings-per-share, sending share prices higher. This has the genial side effect of making executive-owned stock options way more valuable.

When people talk about “the financialization” of the economy, this is one of the chief symptoms they’re talking about. Activity in the real economy is replaced with accounting semantics.

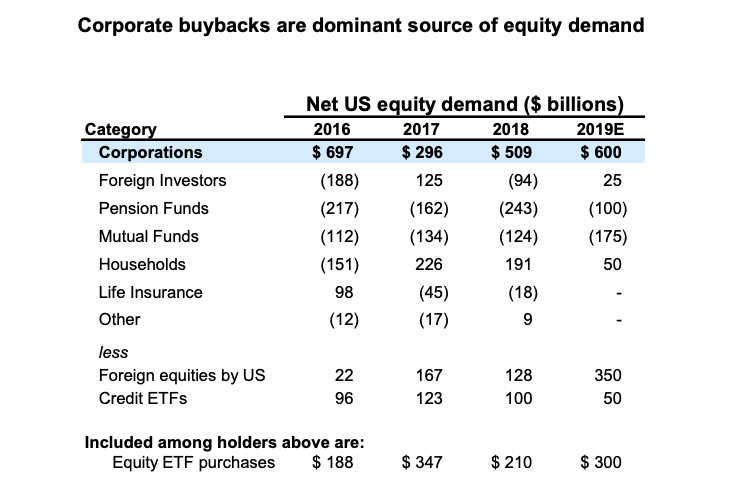

It turns out that share buybacks are now the dominant source of demand for equities. This is very interesting.

It’s interesting because it creates an important dependence on cheap credit in the economy:

- investors, retirees, pension funds3 have been driven out of “safe” bonds and into equities and riskier credit (corporate bonds) in a search for returns, so there is a systemic dependence on the stock market going up or at the very least retaining its value

- but the dominant buyer of equities are companies themselves (see table above), funded by cheap credit,

- so share prices are largely contingent on credit remaining cheap…

A quick note on pensions

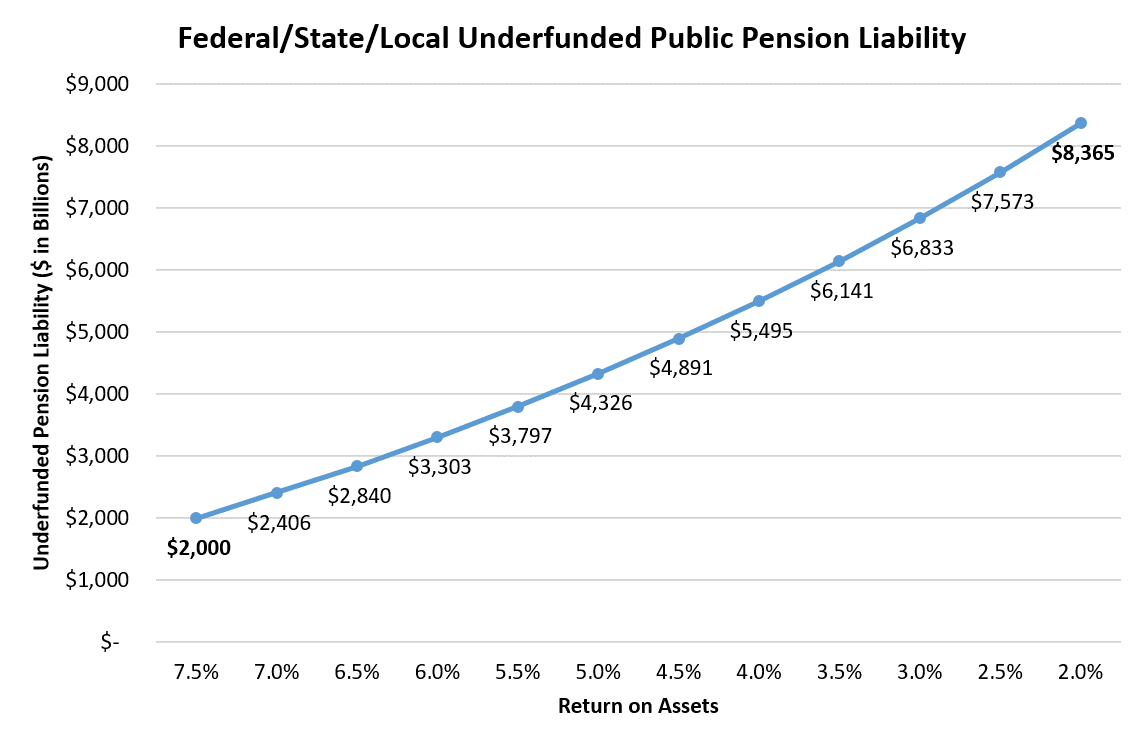

Public pensions in America probably merit their own post because they’re so horrifying, but the short version is that their prospects for solvency are not good. Even assuming a starry-eyed rate of return (7.5% per year), they’re still underfunded by $2 trillion.

There’s no risk-free way to get 7.5%. In order to get returns like that, you have to expose yourself to the equities market or, as is commonly the case these days, low-grade corporate debt. Under normal circumstances, seeing price volatility and riding out periods of loss is a guarantee for the kind of assets that net you 7.5% per annum.

If we assume that pensions get a more realistic rate of return, the unfunded liabilities rise to as much as $8 trillion.

Keep in mind, this 7.5% of return is expected in a world where most government debt is now negatively yielding.

In the desperate search for return, pensions are increasingly relying on large positions of risky allocations. For example, the New York State Teacher’s Retirement System owns $35 million of BBB-rated General Electric bonds. If the GE fraud story has any merit, those bonds may be downgraded to BB which would compel all pension funds nationally to unload the bonds. The funds would sell at a sizable loss and probably crash the corporate bond market.

Because of this chase for yield, the stability of our pension system is now predicated on the stock and corporate bond markets forever performing. There is not good historical precedent for this.

This is what Bitcoin is for. Pensions could juice their returns for far less risk by selling off their large allocation of garbage BBB corporate bonds, almost certain to implode or suffer downgrades in a recession, and placing their risk in a much smaller percentage allocation of Bitcoin.

If pensions are reliant on risky assets for solvency, this means they are now reliant on cheap credit for solvency.

The huge problem starts when and if

- credit doesn’t get cheaper: slowing and heavily indebted companies like GE and AT&T won’t be able to keep buying back and their share prices will fall significantly,

- this puts a drag on the stock market and potentially creates downgrades in corporate credit, a disasterous outcome because

- by law, pension funds are now forced to sell masses of recently-downgraded corporate bonds since they are no longer investment grade (IG), sending corporate yields skyrocketing,

- which further drives the stock market lower as companies become unable to pay their debt by taking out new loans,

- which further batters pension funds and investors.

As you can imagine, this could get really, really bad. Really bad.

Imagine you’re a retiree who’s been forced into the equities market because you started saving late or you otherwise can’t afford low rates of safe credit. You put 80% of your money into equities. Then one day the process above triggers and your wealth halves as the market crashes. This applies equally to pensions.

This is what Bitcoin is for. My guess is that Bitcoin will not be hit nearly as hard as the equity market will, assuming its price doesn't appreciate in a scenario like this — a scenario I'd argue Bitcoin was designed for — if it functions as a safe-haven asset. This is because institutional ownership of Bitcoin is almost nonexistent at the moment. In a rush for the exit (liquidity), large institutions will be selling off risk assets, but I don't think these institutions have any substantial volume of BTC to sell.

The kind of ownership that would be compelled to sell in a situation like this, "weak hands," have already been shaken out of their positions by BTC's volatility. The remaining owners are in it for the longterm. It's my guess that in a downturn, BTC's relative price will be neutral to positive.

The equities market, having been stoked up on easy credit (now painfully dry) may well see a 60-70% decline. Returning to current levels won’t be in the cards for years, maybe decades. We’re talking about a depression and a bunch of people who are no longer able to fund their retirement. It’d be bad.

QE forever

So anyway the above is all theoretical, because there won’t be a crash… not in the form we’re used to, anyway. The government basically can’t let this happen. They have to keep the liquidity (read: cheap credit) flowing or else we have, basically, a complete collapse in equities and low-quality debt, and therefore in public pensions (who own large amounts of these things). This starts to get to, like, civilizational severity.

Central banks will have to keep creating money to keep credit cheap so that companies can continue to buy back their own shares and prop up the equity market. This will continue to increase the money supply and will further exacerbate bubbles in real estate and equities. These bubbles will steadily widen the divide between the have-assets and the have-no-assets in America.

The sort of recession that most people expect eventually may never come, since it can’t be allowed to come. We may have entered a new monetary regime after the fireworks in 2008.

This is what Bitcoin is for. Central banks will continue easing until there is nothing left of their currencies; I can't really see an alternative. There's no soft landing out of this credit-fueled asset bubble. There's no clean way to deleverage the pile of debt corporates have taken on.

Historically gold has been a safe haven refuge in times of contraction and inflation, and I own some small amount, but I'm no great fan. Gold is impractical: it's hard to verify, hard to custody, isn't easily divisible, and just feels kind of outdated. The only easy way to buy exposure to gold (ETFs) are still just a paper proxy for the real thing. They're subject to the same kind of risks if there's a huge crash and financial markets are ordered to a halt. Bitcoin maintains liquidity through such a crash because governments can't stop its ability to perform transactions.

Unlike gold, the authenticity of a Bitcoin balance is immediately verifiable with off-the-shelf consumer electronics, and anyone can safely custody it themselves regardless of amount.

It can't be confiscated. It's perpetually and internationally liquid. It doesn't know borders and gives final settlement in hours. It makes capital flight trivial and open to people who aren't fabulously rich or well-connected. Nobody's sure yet, but for these reasons I think there's a decent chance that Bitcoin will function as a safe-haven asset, much like gold, in a significant downturn.

The macro picture

So far we’ve mostly just been talking about troubles in the US domestic economy. Things get really spicy when we start talking about the increasing international disgruntlement with the US dollar.

Since the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, the US dollar has had the “exorbitant privilege” of being the reserve currency of the world. This has meant that there’s always a healthy demand for the dollar, which in turn stokes reliable demand for our government debt in the form of Treasuries (well, until recently). This has let us run big deficits without worrying too much: there will always going to be other countries waiting in line to roll our debt by buying Treasuries, right? They want to buy oil, don’t they?

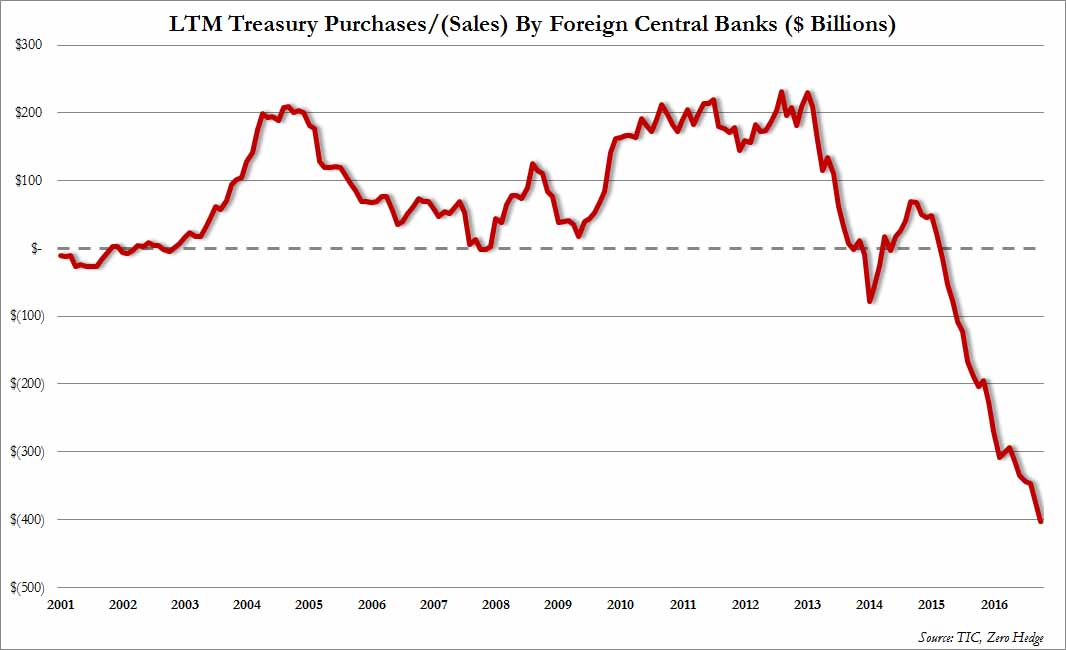

Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like this will last. Foreign banks have stopped buying US treasuries at an alarming rate.

US sovereign debt doesn’t even have a yield advantage anymore even though treasury yields are nominally positive. It turns out that once foreign investors hedge for currency risk, US bond yields go even more negative than their European counterparts mentioned early in the article.

And today: Absurdity that the US w/ at least $800bn net in Treasuries to still be auctioned this year has the least attractive (most inverted) G10 curve and missing foreign end buyers that have been "priced out of the market" pic.twitter.com/Lpkjimi9Nr

— Andrew W. Park (@apark_) August 21, 2019

Foreign central banks may not be buying our treasuries, but they’re sure buying gold. Why would they be doing that? Gold’s a barbarous relic, just shiny metal.

The writing’s on the wall. The rest of the world is getting tired of funding another country’s obviously-unsustainable programs like social security and medicare while simultaneously being vulnerable to dollar-based sanctions. Budget deficits continue to grow at record levels ($234 billion for the month of Feb 2019 and we’re on track to hit a record $1 trillion for the year). Trump’s unhinged Twitter indulgences are a nice foreground to the mind-numbing 222 trillion dollars of on- and off-balance sheet debt the US has set itself up for. Even if the USD is a convenient tool for most countries now, the numbers are unworkable: the US is at some point going to have no choice but to print its way out of a massive debt.

The coming years will continue to see lackluster Treasury demand, hoarding of gold by central banks, and more calls to replace the dollar with digital currency.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney took aim at the U.S. dollar’s “destabilising” role in the world economy on Friday and said central banks might need to join together to create their own replacement reserve currency. https://t.co/NbPbqRT3vX

— Timothy Aeppel (@TimAeppel) August 23, 2019

Politically-favored economists like Bernie Sanders’ Stephanie Kelton will continue to shift the Overton window towards Modern Monetary Theory as an expedient way for politicians to completely disregard deficits and breadwin for their constituents. MMT has an inescapable gravity because it’s politically palatable on both ends: politicians love spending money without having to tax, and constituents love free stuff. You will continue to see MMT in the form of a Green New Deal or some kind of Republican-friendly equivalent, probably relating to infrastructure, and deficits will launch into the stratosphere.

Our ability to get funding from the rest of the world will wane concordantly, and some combination of the Fed, the Treasury, and more loose fiscal policy will coalesce to manufacture remarkable amounts of new money. The resulting inflation will be historic.

This is what Bitcoin is for. Bitcoin is an accessible insurance policy against this increasingly likely dollar endgame for anyone who wants it.

Yes, central banks are buying gold and will likely continue to do so. Maybe some even have the intent of reforming the monetary system to sit on top of some kind of gold standard 2.0. Rumors circulate that China is working on a gold-backed cryptocurrency.

The reality is that we can never credibly return to a gold standard. Repatriating gold to do final settlement is incredibly costly and error prone. Even setting aside practical difficulties, gold (or anything gold-backed, whether it's digital or not) will always come with counterparty risk. When Nixon ended the redeemability of dollars for gold in 1971, the die was cast. You can only stain that shirt once. Is China any less likely than 1970s US to suspend gold convertibility when the going gets tough?

Bitcoin is fully digital bearer asset and as such it has no counterparty risk. Final settlement occurs indisputably within hours, not weeks. The cost of storing it is negligible. Cryptographic features like multisignature schemes and scripting abilities like timelocks enable a trustless programmability that makes it a completely new kind of financial asset, which is basically just a bonus on top of its killer feature: hardness as a money and suitability as a safe-haven asset.

It only gets crazier from here

I’m not sure that Bitcoin will work in the way that I think it will. Nobody is. But I am sure that if the narrative I spell out above is anywhere near right, the financial system in its current form is in for an abrupt change in the next few years. I am sure that there’s no coming back from the government largesse that materialized in 2008, both in terms of the reliance on credit it introduced and the precedent for significant intervention that it set.

The kind of central bank interventions we’ve seen in the past 11 years are without equal. Regardless of political affiliation, most people who’ve been watching finance acknowledge we’re in uncharted territory. The average life of a fiat currency is 27 years, and since going off the gold standard (which I’m not necessarily defending), the US government has been allowed to engage in an inflationary frenzy that has no sign of slowing down.

Bitcoin is designed, intentionally or incidentally, as a near ideal tool to have access to when this level of turmoil hits global markets, when governments start to engage in never-before-seen monetary experimentation, when Treasury departments and other political institutions start to lose their credibility. Trustless settlement makes Bitcoin the ideal “currency of enemies” and censorship resistance means unconditional liquidity.

This doesn’t mean that Bitcoin will actualize on its potential in whatever next crisis lies ahead of us, but it would seem foolish not to have a small amount of your portfolio betting that it will, whether you’re a pension desperate for yield or a millennial like me, disenchanted with almost every other option.

Follow me @jamesob.

Shouts to Luke Gromen, Ben Hunt at Epsilon Theory, Danielle DiMartino Booth, Raoul Pal, Jeff Snider and Erik Townsend at MacroVoices for getting the word out on this stuff.

Resources

- Is a US recession coming? by Raoul Pal

- Luke Gromen on MacroVoices talking about the dollar end game

- Dave Collum’s 2018 Year In Review

- The Bullish Case for Bitcoin by Vijay Boyapati

Thanks

Thanks to William O’Beirne, Luke McGrath, Jeff Vandrew Jr, and Neil Woodfine for reading an early version of this article and providing feedback.

Footnotes

-

Why didn’t all this money result in rampant inflation? Because the Fed started paying interest on excess reserves (IOER), depository institutions hold a lot of this new money in reserves at the Fed and get paid an unnaturally high interest rate to do so. Note: readers have pointed out that my explanation here probably isn’t correct. We didn’t see rampant inflation likely because banks cannot use reserves to lend. See here - thanks to David B. ↩

-

This should be immediately and obviously sisyphean but hey nobody’s perfect. ↩

-

American public pension funds are underfunded by anywhere from $2T-$8T depending on who you ask. ↩